|

In October of 1967, Company A

was working on Route 509, a Vietnamese National highway that ran west

out of Pleiku into Cambodia. Actually, this National Highway was a dirt

road, but it was a National Highway nonetheless. Our job was to put in

metal culvert pipe with sandbag headwalls where the road had washed out

and to build two timber trestle bridges over rivers.

I was the radio operator for the 3rd Platoon of Company A. At each

culvert location, we would unload a dozer from a flatbed semi-trailer

and push a trench across the road for the assembled culvert to lay in.

The culvert came in 2-foot long section halves. The halves were bolted

together into a section and the 12 to 15 sections were bolted together to

make the culvert. It was time-consuming work, usually taking a day or more

to assemble a single culvert.

At one particular location, we had 3 culverts to install so we knew we would

be there for 3 or 4 days.

My job as radio operator was to sit on the flatbed trailer that hauled the

dozer with my radio and rifle next to me and call on the radio for backfill

or culvert sections or sand for sandbags or anything else we needed. I was

also on the lookout for anything, which might be a danger to our squad, ready

to call in tanks or helicopter gun-ships or artillery support in case of attack.

My radio was a backpack, battery-operated unit, a PRC 25, which stood for Portable

Radio Communication with a 25-mile range. Everyone called it a Prick 25, and I

was the Prick 25 operator.

Since we were going to be in the same location for 3 or 4 days, I was not looking

forward to seeing the same scenery all day from my flatbed perch for that long,

but there was a Montagnard village nearby and I knew that the kids would come

from the village to watch us work. Montagnard kids were special. They would

not mob you like the Vietnamese town kids from Pleiku and try to pick your pockets

or steal your watch from your arm. Instead, they would stand and watch or look

at you and would not approach until you motioned them to come closer. Then they

would come close to see what you wanted, but would never beg or steal as most

Vietnamese kids would do.

The nearby Montagnard village was surrounded by a high bamboo stockade fence for

protection and, in addition, it had a 4 foot deep ditch outside the fence filled

with punji stakes, which are sharpened bamboo stakes driven into the ground,

sharp end up, which would make anyone think twice about jumping over the ditch.

We had not been working long the first morning when I saw some kids come through

a hole in the bottom of the stockade fence, each one tiptoeing his way through

the punji stakes and waiting for the next one to come through. About 10 kids

came through one at a time from the safe side of the fence. Then they walked

in a group across the field of grass separating us to watch us work. The group

ranged in age from 12 or 14 years old down to 5 or 6 years old as near as I could

tell. They stood and watched us and smiled and looked embarrassed. I sat on the

lowbed and watched them watching us.

When I beckoned them to come closer, they came forward as a group. In the back of

the group was a little girl, the smallest of all who looked as though she had come

along only because she did not want to be left out, but was not at all comfortable

about being this close to soldier with a gun and hand grenades.

The older boys came close and asked to look through my binoculars. I could converse

with them using what little Vietnamese I knew and the little bit of English they

knew, plus a little bit of French that they had probably learned from their parents.

They called my binoculars “jumelles”, which is the proper French word for them,

meaning “twins”. They looked through the binoculars and I gave then some c-ration

cigarettes that I used for trading, but my eyes kept returning to the little girl.

She did not trust me and made sure that another kid was between us at all times.

And she was afraid. When I looked at her, she would look at the ground while still

watching me out of the corner of her eyes. When I smiled at her, she hid behind another older kid. She was starting to get to me, this beautiful, dirty-faced child, because she seemed so afraid of me and I didn’t know why. I tried to show her that she did not have anything to fear from me, and I stood up and held out my hand and walked toward her. She reacted by running away all the way to the safety of stockade fence, while the other kids laughed at her fear.

The rest of the kids came and went all day long and the little girl would return

with them and if I moved in her direction, she would run away, but each time she

ran a shorter distance, so I knew I was getting to her too.

The first day ended with me wondering how I was going to get through to this kid,

to let her know I was her friend and that she had nothing to fear from me.

The second day we left our base camp and returned to the culverts, and, after

checking the area for mines, the platoon continued their work. I got back on

the lowbed with the radio and got out my pad of paper and started writing a

letter. I kept an eye on the stockade fence and before long the kids came through,

3 older boys from the day before and the little girl.

They walked across the field and the boys walked right up to me, but the girl stopped about a 100 feet away. She was taking no chances with only 3 others to hide behind. I told one of the boys to go ask her to come on over and he went to her and spoke to her and I saw her head shake emphatically “no”. The boy returned and not knowing how to explain in English, simply shrugged his shoulders.

I gave the boys more cigarettes, which they promptly lit up. Soon two of the boys left and one stayed with me and still the girl just stood at a distance and watched us. I was going crazy trying to figure out how to communicate with her.

Suddenly and idea struck me. I knew how to make a bird out of folded paper so I took a sheet from my writing pad and made a bird and showed the boy that by holding it by the bottom and pulling on the tail, its wings would go up and down. I told him to give it to the girl and tell her it was a gift from me. He ran over to her and I could see him demonstrate how to make it work. She grabbed it away from him and did it for herself.

I was totally unprepared for what happened next. She dropped all pretenses of fear and shyness and was overtaken by delight. She jumped up and down, she screamed and laughed. She ran around in circles and rolled on the ground. She got so excited that she grabbed a hold of the boy and they jumped up and down together until they both fell down, and all the while, she was screaming and laughing. She ran off by herself and stopped to make the wings move again and started jumping and laughing again. I didn’t know what to think. Was this the only toy she ever had? Or was it the only gift she had ever received? It may have been. As for me, it was the only time I had ever seen such a reaction to anything. I thought to myself, ”I think I got through to her”. And she ran back through the hole in the stockade fence.

The day wore on, but no more little girl. That night, I told some of my buddies what had happened, still not believing or comprehending it.

The next day, no children came. This was very significant. We became very nervous and watchful when no kids were visible. It could mean that their whole village knew something about nearby Viet Cong activities that we did not know. It could mean that they were being kept safe from an expected attack on us. I kept my radio hidden, as it would draw fire to me since I was the one who could call for help. We were 10 very edgy GI’s.

In my efforts to make myself as inconspicuous as possible, I didn’t notice one kid come through the fence. But once when I looked toward the fence, there she was, standing alone in the field. I waved to her and she only looked back. I wondered why she was out alone, and went about keeping a lookout, but each time I looked in her direction, she had moved a little closer.

I decided to play a game and see how close she would come if I wasn’t watching. I looked in her direction whenever my curiosity became too great to resist and each time, she would be standing motionless, but closer than the last time. It took all the discipline I could call on not to look in her direction for several minutes, but I finally looked toward her, and there she stood, 10 feet away, smiling at me. She had come alone to tell me something.

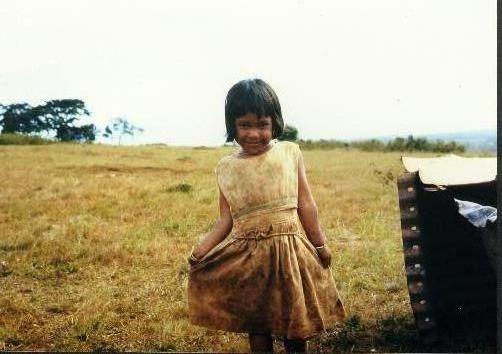

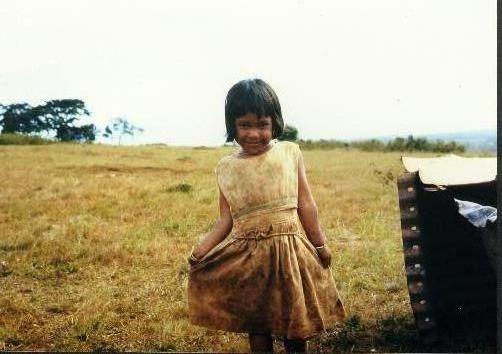

We stood smiling at each other and neither of us spoke. Not knowing anything else to do, I turned and picked up my camera and squatted down to take her picture. She even posed a little although she was still very shy, as the picture shows. I stood up again and we just looked at each other and smiled. Then she turned and ran back to the stockade fence and disappeared. Our hands had never touched nor had a word ever passed between us, but our hearts had met. My paper bird had told her “I like you and I mean you no harm”. Her long walk alone had said, “ Thank you, I’m not afraid of you anymore”.

I saw her again the next morning. She came through the fence alone again and stood far away. I waved to her and she waved back. She stood in the same spot for an hour and I looked up occasionally and waved to her and each time she waved back. When I looked up again, she was gone. I had seen her for the last time.

We left that day and finished our work on Route 509 shortly after Thanksgiving. We returned to Pleiku and never saw that red dirt road again. In February of 1968, during the Tet Offensive, I could see fierce night-time battles being fought near her village from the base camp where I spent the nights in a steel and sandbag bunker. I prayed for her safety. I wondered if the fear that had possessed her earlier had returned. I am sure it must have.

I still wonder about that little girl. I wonder if she survived the war and, if she did, does she still remember the paper bird and the young soldier who gave it to her? I hope she does, because I will always remember her long

walk alone through the grass to tell me “Thank you”.

Doug Young (October, 2009)

|